GDC 2014: Gaming & the Humanities

Recently I gave the following talk as part of the 2014 Game Developers Conference panel:  U.S. National Investment in the Future of Games?  The panel was arranged by Noah Wardrip-Fruin (associate professor of computer science and co-director of the Expressive Intelligence Studio at UC Santa Cruz), and other participants included William S. Bainbridge (Program Director for the National Science Foundation) and Elaine Raybourn (Principal Member of the Technical Staff in Cognitive Systems at Sandia National Laboratories, on assignment from to the Advanced Distributed Learning Initiative, Office of the Deputy Secretary of Defense).  You can read Noah’s framing remarks here.

In an earlier session for the GDC Education Summit, I provided a review of many of the games-related projects that had been supported by NEH over the years, but as this panel’s audience was more likely to include a stronger mix of industry, I wanted to speak a bit more broadly about the kind of considerations that might go into a humanities-centered project, and the challenges of working with humanities material. [Note that the content that follows reflects my opinion and should not be taken as official NEH policy.]

Gaming & the Humanities: a description, a challenge, an appeal (& a rocket cat)

With my ten minutes, I want to talk about gaming and the humanities, and in doing so offer three things: a description, a challenge, and an appeal.

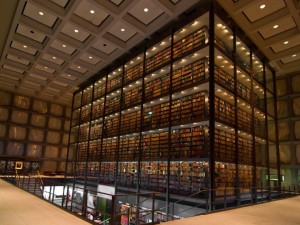

The description is this: I work in the Office of Digital Humanities, which is a small office at the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). NEH is an independent federal research funding agency for humanities subjects like history

literature,

philosophy, art history, and archaeology, and the study of media like film, TV, and (yes) video games. Â (We are to the humanities as NSF is to the sciences, with some cross-over in subjects like history of science, anthropology, archaeology, and so on.)

NEH gives grants to nonprofits, universities, museums, and other cultural organizations for all kinds of work, and those organizations in turn often collaborate with developers, documentary film makers, designers, and programmers in developing these projects.

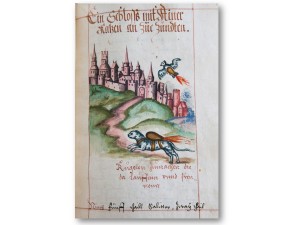

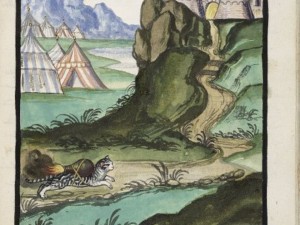

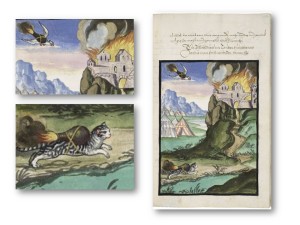

Some of the scholarship we fund matches the kind of ideas you might have of literature scholars or art historians: grants to write books on Shakespeare or to digitize a rare manuscript in an archive like those with Rocket Cats (like this 1607 German manuscript held by the Folger Shakespeare Library). Apparently there are several of these images from 16th and early 17th century manuscripts, cats and birds with a flaming jetpack of hate attached to their back, used to infiltrate and burn villages and castles. At least, that was the idea [see more about rocket cats at Atlas Obscura].

Here’s another one (this one from Penn State).

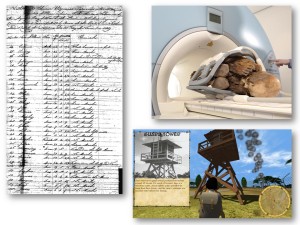

And we fund some pretty innovative work, and weird collaborations, like Egyptologists and cardiologists using large-scale data analysis and MRIs on all the world’s mummies to better understand heart disease and the cultural practices of ancient Egypt. We have wide-ranging interests.

If you want to learn more about those interests and the kinds of things we fund, I encourage you to visit our website at www.neh.gov/odh

One of those interests is games. Among our more successful ventures is Metadata Games, from Mary Flanagan at Tiltfactor and her team of designers and archivists. Metadata Games is helping crowdsource metadata for huge amounts of digitized cultural heritage — pictures like these — making them in the process more discoverable. Mary received both a Start-Up Grant and an Implementation grant from the Office of Digital Humanities to support this work.

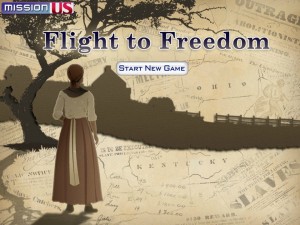

We’ve also dipped our toe into funding some educational games. With the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, NEH helped support Mission US, developed by a team at WNET (NY Public Media), a series of episodic adventure games on topics like the events leading up to the American Revolution,

or the flight from slavery and the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

Mission US was supported through our Division of Public Programs, which is about to release a new program–Digital Projects for the Public–that can support games that inform the public about humanities topics. There’s an informational sheet in the back if you’re interested in this new program.

The Office of Digital Humanities—where I work—has funded a variety of game and game-like experimentations through a program called Digital Humanities Start-Up Grants, which encourages early-stage prototyping,. These grants are mostly low level, 30-60k to experiment, try out new things, take some risks, see what works and doesn’t work, and share your results. I’ll talk about a few of them in a minute.

But that’s the description of what NEH is and does. And in that description, you likely picked up on some of the things that are important for scholars to do their work. They use primary documents–old manuscripts like that rocket cat–but documents can come in the form of oral histories, or novels or poems or old newspapers or even financial or shipping records. With that evidence and their own knowledge of events over time, scholars piece together the best understanding they can of the historical record. I’m sure to many of you this sounds fairly familiar.

It’s a quest, of sorts.

And so here’s the challenge: building games about humanities topics–games that really draw on the historical record, that show an interpretation of history, or literature, or art — is really kind of difficult. The humanities are messy, and the historical record is almost always going to be incomplete, as histories — and stories — often are. But we try to use this knowledge to understand how things work on a macro scale and on a micro scale. Let me give you an example.

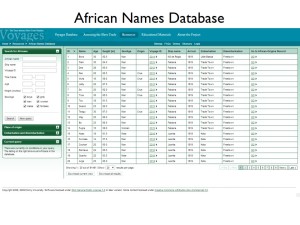

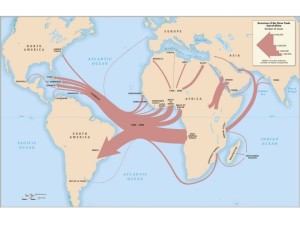

This is the Trans-Atlantic Slave Database, developed by a team at Emory university led by David Eltis, a historian, and Martin Halbert, a librarian. This represents years of labor–the creation of datasets that inform this project started in the 1960s, and the team of developers and historians involves a ton of people, and decades of scholarship.

Overview of the slave trade out of Africa, 1500-1900, from slavevoyages.org (click image to see other maps)

And they’ve created a pretty good record of how the slave trade worked, where the ships went, and from what ports,

but they’ve also been able to start reconstructing who these people– slaves taken from their home, shipped overseas–who they actually were, at least as best they can, recorded here in the African Names Database.  This is the macro and the micro, the broad idea and the individual person. How do you translate this into a game environment, into a series of mechanics, a set of rules?

The whole of it, not just the movement of people (this broad idea of migration ….

… and movement, the journey, which is so important a theme in the humanities and in games),

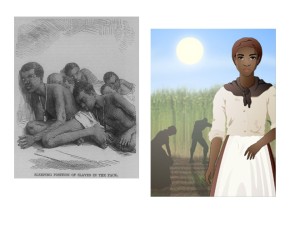

but also the complicity of it, the suffering of it, the confinement of it (contrasting moments of mobility/confinement also so important in the humanities, an idea so elegantly captured in Train)…

the sorrow of it (explored thoughtfully in Terry Cavanagh’s retelling of the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice)?

How do you tell the story with sensitivity and respect to the historical record,

On left: Slaves Liberated from Slaver “Zeldina”, Jamaica, from slavevoyages.orgOn right: screenshot from Mission US: A Flight to Freedom

but also with sensitivity and respect to the individual lives involved?

As you can see from the images, there are efforts and models out there, not just something like Oregon Trail, from which we all learned about migration and dysentery, but also Journey, and Train, and Don’t Look Back, and even the historically informed Advanced Squad Leader and other wargames, which generate so many volumes of historical written record to inform their counterfactual play. But balancing the counterfactual and historical record, the macro level and the micro, the big picture and the individual story is really what I feel is the challenge of gaming in the humanities.

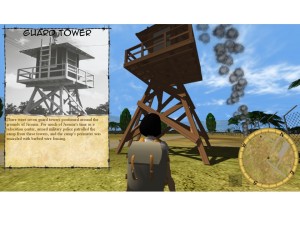

Through the Start-Up Grant program, we’ve also funded small experiments, such as telling one girl’s story of living in Japanese internment camps in the Jim Crow South during World War II, through Emily Roxworthy’s (UCSD) Drama in the Delta.

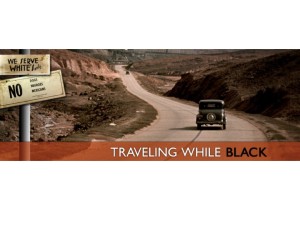

Or this recent transmedia project that received a small Start-Up Grant—it’s just getting started–called Traveling While Black — a collaboration between filmmaker Roger Ross Williams, game studio Playmatics, and a deep advisory board of historians and scholars. It aims to explore what it meant to travel in the Jim Crow South when segregation meant that black travelers often couldn’t find a hotel, or a place to eat, or a place to buy gas, or even a place to use the bathroom.

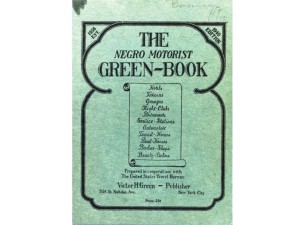

It centers on an extraordinary textual document, the Negro Motorists Green Book, published between 1936 to 1966 by Victor Green, a mailman and travel agent in New York. For more than thirty years, this book provided a list of safe havens and warned of dangerous locations.

These are just some initial steps. It’s a huge challenge, and not one that I believe either humanities scholars or game designers will be able to tackle alone. I’m watching with keen interest the work of designers like Tracy Fullerton, with Walden and Night Journey,

and Navid Khonsari’s development of the first episode of Revolution 1979. Both are drawing on cultural contexts, textual evidence, and scholarship to inform design.

So that is the challenge–one that I believe can only be truly addressed collaboratively, drawing on mutual expertise, and growing those rare talents that operate in this hybrid space. I promised a description, a challenge, and a appeal. Part of my appeal is this: if you’re interested in these challenges, or if you’re a person who works in these hybrid spaces, I’d love to hear from you. I’ll note that we often ask game designers who have knowledge of the humanities to serve as reviewers for grants, and even more generally I’d be grateful to have your feedback on how we might address challenges like these with national funding. I also encourage you to consider our grant programs if you’re working as–or with–a nonprofit or at a university.

To conclude, my final appeal is this: save the rocket cats.

What do I mean by this? The games being produced, that have already been produced, comprise an amazing corpus of cultural heritage material, and this includes the records of how you’re figuring out really difficult and fascinating challenges and creating genres of play.

And scholars now and in the future will want to know how that is done, ways that you approached the problem, methods that you tried, scholarship you used to inform your game, just as they try to understand the form and content of a novel by William Faulkner or Zora Neale Hurston — not just their final novel, but the notes and papers and letters, all that contextual material that shaped the novel. That’s how scholars create an interpretative framework.While I know some companies and game labs have local archivists, I also know — mostly through the amazing work done by the Preserving Virtual Worlds project (funded by the Library of Congress and the Institute for Museum and Library Services), that most do not. And even if the executable file of your game remains available, I’d like to leave you with a thought from literary scholar Matt Kirschenbaum, who has been working on born-digital preservation for a while.

From “Virtuality and VRML: Software Studies After Manovich” at electronic book review [click to visit]

These are your archival materials, as much as the game itself.

And the lesson of the rocket cat is that you don’t know what hidden Easter egg, what manuscript, what “material trace” will cause a future scholar’s heart to swell with joy, or what trends or insights scholars and enthusiasts will find when they take a look at your work with the eye of a critic, a historian, an anthropologist, a literary scholar, an art historian.

The humanities employ a wide array of methods, and just as they would dig into the archives to understand the slave trade, or use MRI scans of mummies to understand ancient Egypt, or design a game to understand the complex racial relations of an internment camp placed in the deep South,

so too do scholars, even now, want access to the archives, tools, code, memos, and especially, when possible, game analytics. There may well be all sorts of legal and competitive reasons that one can’t share all of that, but I appeal to any of you have access or control of these materials to share what you can, and, even more importantly, to work with scholars and librarians to preserve the rest in a dark archive until you can share it. What you do is valuable, and our mission at the NEH is to help preserve and interpret our shared, valuable cultural heritage.

Archives

- February 2016

- April 2014

- March 2014

- April 2013

- March 2012

- January 2012

- March 2011

- February 2011

- February 2009

- January 2008

- September 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003

- September 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- April 2003

- March 2003

Categories