Emerging Genres, Progressive Readings: Games, Fiction, and Narrative Play

This brief paper was offered as my contribution to the Close Playing: Literary Methods and Video Game Studies roundtable at MLA 2012 in Seattle.  I very much appreciate the dynamic audience (a full house is a wonderful thing for the final session of a 4-day conference) and a terrific group of colleagues to present alongside: Mark Sample (GMU),Edmond Chang (Univ. of Washington), Steven E. Jones (Loyola Univ., Chicago),Anastasia Salter (Univ. of Baltimore), Timothy Welsh (Loyola Univ., New Orleans), and Zach Whalen (Univ. of Mary Washington).  The format involved 6 six-minute papers, which allowed for nearly an hour of active discussion.  Many thanks to Mark Sample for keeping us on task.

[It should not need to be said, but: opinions expressed are those of Jason Rhody and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the National Endowment for the Humanities on gaming, narrative, or any other topic.]

—

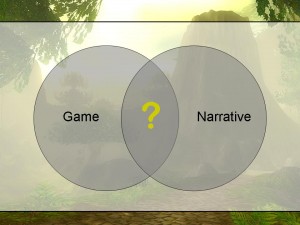

These remarks stem from a much longer book-length project called “Game Fiction,†in which I offer an approach to moving past what I considered a discourse about games and narrative stymied by absolutes rather than models.  Despite the fact that some computer games are clearly a site of narrative production and consumption, the relationship between narrative, on the one hand, and games, on the other, has remained somewhat uneasy, if not contentious, within the critical literature for both game studies & narrative theory.

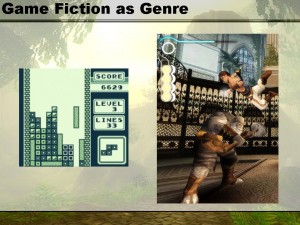

As a path forward, I’ve proposed a rubric under the term “game fiction,” which I identify as a category of game that draws upon and uses narrative strategies to create, maintain, and lead the user (player) through a fictional environment in order to actualize a narrative and ludic goal.

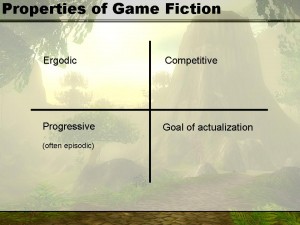

I offer four principle properties of game fiction–they must be ergodic, competitive, progressive, and hold a goal of actualization (in combined narrative and game terms).

I don’t have time to fully detail each of these qualities, but it is important to note that these qualities are NOT absolutes; they serve as an analogue scale so that we can approach the issue with appropriate levels of nuance.

What drew me to this project was the fact that we still lacked an adequate vocabulary to address narrative in games.  I’m less interested in questions of “are they or aren’t they,†and much more interested in questions of When are they narratives, and How are they narratives? These are questions of genre, and as we all know, the border-cases are often the most interesting cases of all.

So I’m less interested in how Tetris is not Prince of Persia, but more how  StarCraft is different from StarCraft (the multiplayer map is on the left, and the single-player map is on the right… note the differences in symmetry).

In taking this turn toward genre, I’d like to identify two key changes where game fictions stand out from other fictional genres & how we might rethink this shift and understand the changing face of narrative in a world increasingly governed by computational function. I further believe these issues are both part of the root cause for the narratology/ludology debate and further reflect the value of studying games from a literary perspective.

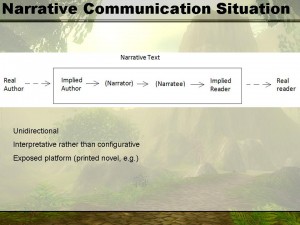

First, there is fundamental shift in the narrative communication situation, as articulated by Seymour Chatman.

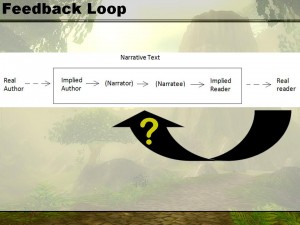

When we introduce a consistent feedback loop that involves player input, it creates a new dynamic of power and requires altered models of production and consumption, transmission and exchange.

Second, the black box that represents the narrative text in Chatman’s model becomes, with a game fiction, quite literally a black box of computational operations, which are often hidden or obscured to create the puzzles and challenges that are foundational to gaming.

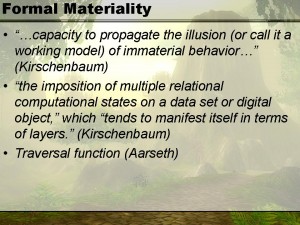

So there is a need to explore what Matt Kirschenbaum calls the formal materialities of software, a call reflected also in the rise of software studies and platform studies.

To better understand how plotted events are embedded within a game fiction, we must move beneath the interface to explore relationships of narrative setting to database, for example, and of the quest to the query.

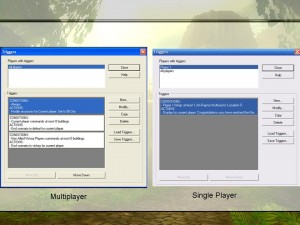

StarCraft, a real-time strategy game with both single and multi-player modes, serves as a particularly useful example of how the single player works as a game fiction while the multiplayer does not. While both single and multiplayer versions are ergodic and competitive, only the single-player maps tend to be progressive with actualizable moments embedded in the game.

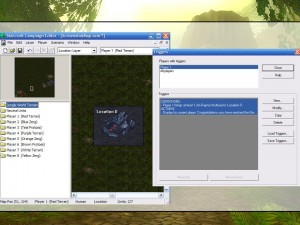

Single-player matches in StarCraft have clearly articulated, deeply encoded requirements for staged progression– Mission Six of the Terran campaign (with triggers and pre-planned events annotated here on the screen) is a useful example. The properties of data, their placement and use in the game can tell us a great deal about how narrative functions in game fictions. Despite modern methods for encoding games, game fictions still function like early data models, which were 1) primarily hierarchical, 2) stressed parent-child or networked relationships between data sets, and 3) were, above all, navigational. Hierarchical and simple network databases often required user knowledge of the data design because navigation and query occurred via predefined relationships. Navigation, query, and data were tightly intertwined. These principles hold true for game fictions, which tend to be highly navigational and spatial.  The stronger the tie between an objective and a location, the stronger the tendency towards progression and actualization.

You can use map modification tools like StarEdit to show how the design is staged. A designer would embed data structures within the fictional setting, and then the designer would imbue the data object (here, a battleship) with conditions and actions –precisely the way one programs triggers within typical (non-game) database structure.

The difference between common conditions and actions in multi-player maps versus single-player maps is particularly telling.  The default StarCraft multiplayer maps uniformly rely on three sets of common conditions/actions, whereas the singleplayer maps often invite hundreds of variables (in this case, the player must bring the Jim Raynor character to a particular location) .

The manner in which players engage with data in a representational questing environment still recalls the fundamental concepts of data manipulation language (DML), most colloquially known as ‘the query.’ Commands such as SELECT, UPDATE, DELETE, or INSERT can be mapped to quest objectives such as find, deliver, slay, recover, and so on (in this case on the right, Update Location 0 with a character type). Data is staged to enable plot, and the quest functions as a query.

If the rise of the novel as a form of prose fiction in the 18th century reflected a growing “tendency for individual experience to replace collective tradition,” as Ian Watt argues (14), then comparatively the rise of game fiction could be seen to reflect a tendency towards collective tradition under the guise of individual experience.

Thank you.

4 Responses to Emerging Genres, Progressive Readings: Games, Fiction, and Narrative Play

Leave a Reply

Archives

- February 2016

- April 2014

- March 2014

- April 2013

- March 2012

- January 2012

- March 2011

- February 2011

- February 2009

- January 2008

- September 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003

- September 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- April 2003

- March 2003

Categories

[…] contentious, within the critical literature for both game studies & narrative theory. –Emerging Genres, Progressive Readings: Games, Fiction, and Narrative Play. Related posts (automatic, by […]

[…] Rhody, “Emerging Genres, Progressive Readings: Games, Fiction, and Narrative Play” January 11, […]

[…] Edmond Chang, Univ. of Washington, Seattle; Steven E. Jones, Loyola Univ., Chicago; Jason C. Rhody, National Eudowment for the Humanities; Anastasia Salter, Univ. of Baltimore; Timothy Welsh, Loyola […]

[…] relate to — and change — more traditional domains of inquiry?  Can we see ways to revise theories of narrative based on the introduction of formal feedback loops,  adjust approaches to textual studies based on […]